Visitors to the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, and the neighboring Harvard-Yenching Institute and Library, which share the same building, often remark on the contrast between the neo-Georgian architectural style of the brick and marble edifice at 2 Divinity and the institutions housed therein. In particular, the marble reliefs that adorn the building’s outer walls carry almost nothing that signifies East Asia, and indeed the marble relief map over the main door shows only the Western hemisphere (fig. 1). While the stone lions, a gift to the Harvard-Yenching Institute by the Starr family in 1962, help to mark the building as a center for Asian studies, the contrast remains.

fig 1. marble relief map of western hemisphere above the entrance to 2 Divinity Avenue

This serves as a reminder that the building was not originally designed to house a department for East Asian studies. The main structure was built during the years 1930 and 1931 as the home for a new Institute of Geographical Exploration. This initial purpose explains the distinctive reliefs on the building’s façade.

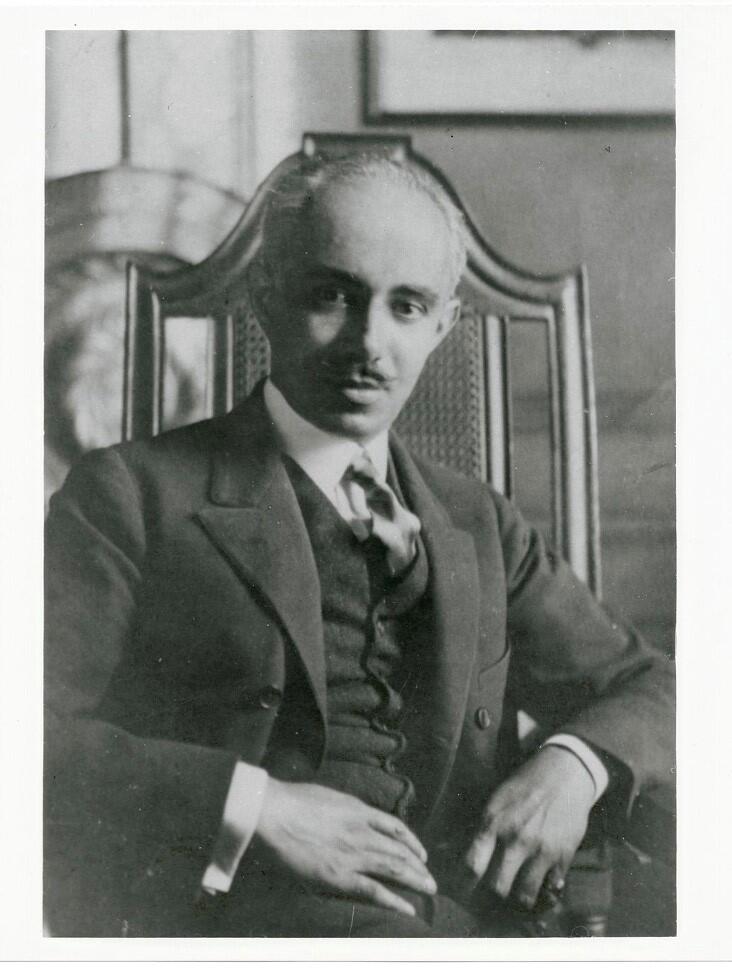

The building was commissioned by Alexander H. Rice with the financial support of his wife, Eleanor Elkins Widener Rice, who came from one of the wealthiest families in Philadelphia. She had previously funded the construction of Widener Library in honor of her son, Harry Elkins Widener, who perished along with his father, Eleanor’s first husband, George Widener, when the Titanic sank in 1912.[1] Widener stipulated that the architect for the new library be Horace Trumbauer & Associates (fig. 2), the firm behind several buildings and lavish homes built for the Elkins and Widener families, including the Newport mansion Miramar, in progress at the time of her husband’s death and completed in 1915.

fig 2. Horace Trumbauer, center, with Eleanor Widener Rice and George Widener, Jr. at the dedication of Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University

The choice of Trumbauer & Associates in 1930 for the Institute of Geographical Exploration at 2 Divinity Avenue is therefore no surprise. The building accords with the symmetrical proportions and neoclassical touches characteristic of other work by the firm. The marble interior, grand staircase, and wrought iron ornamental details evoke the opulence of a residence like Miramar (fig. 3) and demonstrate the kind of extreme wealth that kept the architectural firm in business during the most devastating years of the Great Depression. Although Trumbauer & Associate’s buildings were long attributed to Horace Trumbauer, credit should have gone to the firm’s chief designer Julian Abele (1881–1950) (fig. 4) who designed over one hundred of them, including Widener Library and the building at 2 Divinity Avenue.[2] Acclaimed as the last and best American-based beaux arts architect of the early twentieth century, Abele was also the first African American to graduate with a B.S. degree in architecture in the U.S., which he did from the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture in 1902. Abele’s work long went unacknowledged, a result of both explicit and implicit racial discrimination, as well as a Trumbauer office policy that forbade staff from signing any drawings leaving the office.[3] Numerous institutions have recently begun to redress this neglect, starting with Duke University, whose West Campus includes thirty buildings designed by Abele between 1924 and 1950.[4] In 2020 Widener Library mounted an exhibition on Julian Abele in its rotunda, among the first efforts to commemorate the architect’s contribution to the College’s most central building.[5] Although the comparatively modest structure at 2 Divinity Avenue has not garnered much attention, it has a role to play in telling the history of Abele’s life and work.

fig 3. the grand staircase inside 2 Divinity Avenue

fig 4. Julian Abele, designer of 2 Divinity Avenue and Widener Library

Abele’s elegantly proportioned two-story building at 2 Divinity (fig. 5) owes much of its appeal to the shape and placement of the marble details that accentuate the redbrick façade. Horizontal bands of white stone run the width of the structure above and below the windows and beneath the cornice and dentil molding, articulating the floors of the structure and emphasizing its horizontality. To carve the intriguing cartographic and zodiacal images on the stone, Trumbauer & Associates turned to their long-standing collaborators, the stonemasons of John Donnelly, Inc. of New York.[6] The artisans who worked for John Donnelly Sr. (1867–1947) were mostly Irish craftsman in the United States on a temporary basis.[7] John Donnelly, Inc. was responsible for sculptural carvings on several government buildings in Washington D.C., from the Library of Congress and the Capitol to the bronze doors of the Supreme Court Building, whose bas-reliefs were designed by architect Cass Gilbert (1859–1934) and John Donnelly Sr., and carved by John Donnelly Jr. (1903–1970).[8] While 2 Divinity was nearing completion, the firm began working with Trumbauer & Associates on the iconic Duke University Chapel designed by Julian Abele.[9] The idiosyncratic iconographic program on the Duke Chapel seems to derive from a combination of the carvers’ own knowledge as well as input from specific individuals.[10] Likewise, the cartographic and astronomical imagery on the exterior of 2 Divinity almost certainly reflects the wishes of the building’s client Alexander Rice and his ideas about geographical exploration.

fig 5. façade of 2 Divinity Avenue

After the Harvard administration under President Conant eliminated the Geography Department in 1948 and Rice retired as the Geographical Institute’s first and only director in 1951, the Institute shut down and the building at 2 Divinity reverted to direct university oversight.[11] By the 1950s, the expansion in the faculty and course offerings of the Department of Far Eastern Languages, together with the rapidly expanding library holdings in East Asian languages, exerted a significant strain on its then home in Boylston Hall.[12] Given the new availability of 2 Divinity, it was decided that this would make a good home for the Department. Initially, Far Eastern Languages and the Harvard-Yenching Institute shared the building with the Departments of Mathematics and Statistics. In 1957, the building was remodeled and the expansion, which presently houses the Harvard-Yenching Library, was constructed with funds from the Harvard-Yenching Institute. A new lecture hall called the Yenching Auditorium was created by the architectural firm of Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott with an addition to the rear of the building that carefully matched the style and materials of the original structure. Far Eastern Languages and the Harvard-Yenching Institute shared the building with the Department of Statistics until the space it occupied on the fourth floor of the library annex was urgently needed for the growing collection. From that point forward, the only other organization to share the building was the Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, now the Department of South Asian Studies, which remained at 2 Divinity until its relocation to 1 Bow Street in 2003.

Melissa McCormick

Published March 6, 2023

[1] Eleanor Widener had been with her husband and son on the Titanic but survived by “manning the oars of a lifeboat”; see her obituary, “Mrs. A. H. Rice Dies in a Paris Store,” New York Times, July 14, 1937. The couple had been traveling to deliver thirty silver plates previously owned by Restoration period actress Eleanor “Nell” Gwyn (1650–1687) to the London Museum (NY TIMES Oct. 6, 1915).

[2] Dreck Spurlock Wilson in an appendix in the monograph Julian Abele: Architect and the Beaux Arts (Routledge, 2019) highlights all the buildings of the office attributable to Abele and lists 2 Divinity under the client’s name Alexander Hamilton Rice.

[3] Wilson, Julian Abele, 87.

[4] Duke University launched a year-long commemoration of Julian Abele in 2016 and created several online resources, including a website and video series, and renamed the quad of its Central West campus after the architect. At Monmouth University, The Julian Abele Project delves into the life and work of the architect and explores the history of the most prominent building on campus, “The Great Hall,” designed by Abele in 1929.

[5] Colleen Walsh, “Shining a Light on a Genius,” Harvard Gazette, February 26, 2020. Also see the essays by Elsa Hardy, “In Pursuit of the Marvelous,” pp. 40–41, and by Esteban Arellano, “Excavating Names Lost,” pp. 42–43 in Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum, edited by Sarah Lewis and The Vision and Justice Project (TC Transcontinental Printing, 2019).

[6] The Cambridge Tribune, Volume LIII, Number 36, November 8, 1930, p. 7. A column on Real Estate and Building News reports on the status of the “School of Geography” Divinity Avenue (its brickwork had been completed up to the cornice) and lists the subcontractors involved, most notably John Donnelly, Inc., New York, responsible for the models and carving, and D. T. Ryan Iron Works, Brighton, which provided the “ornamental iron.”

[7] Paula Murphy, “The Irish Imprint in American Sculpture in the Capitol in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Capitol Dome, A Magazine of History Published by the United States Capitol Historical Society, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2018): 30–46.

[8] John Donnelly, Sr. also carved the East Pediment of the Supreme Court (Justice of the Guardian of Liberty), designed by Hermon A. MacNeil (1866–1947) in 1935 and prominently signed his name. The Donnelleys’ process began with designs drawn on paper and then modelled in clay. Notable Donnelley projects in New York City include the Woolworth Building, Riverside Church, Grand Central Terminal, and the statue of George Washington for the New York World's Fair (1939), from the description of the Donnelly scrapbook on architectural sculpture, 1894–1970, New York Historical Society archives.

[9] William E. King, “Construction Laborers Unsung Campus Heroes,” in If Gargoyles Could Talk: Sketches of Duke University (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1997), 94–96. The cornerstone of Duke Chapel was laid on October 8, 1930, exactly one month before the brick edifice of 2 Divinity was completed.

[10] King suggests that the inclusion of a sculpture of southern poet and musician Sidney Lanier (1842–1881), known as “poet of the Confederacy,” could represent a personal choice of Duke’s president William P. Few, a South Carolina native and Harvard Ph.D. in English; ibid., p. 96. Lanier’s sculpture was the right-most figure of a triad of “men of the south” to the right of the chapel’s main portal with Thomas Jefferson on the left and Robert E. Lee in the center. In 2017 Duke University removed the sculpture of Robert E. Lee, and in 2018 decided to leave the original space blank as a reminder of “how the reality and symbols of our past continue to shape our present;” see Duke University’s online introduction to the chapel’s architecture, which includes links to reporting on these decisions.

[11] The demise of Geography at Harvard is discussed in several publications: Neil Smith, “'Academic War Over the Field of Geography': The Elimination of Geography at Harvard, 1947–1951,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 77, no. 2, Taylor & Francis Group, 1987, pp. 155–72; Andrew F. Burghardt, “On 'Academic War over the Field of Geography,' The Elimination of Geography at Harvard, 1947–1951,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 78, no. 1 (Taylor & Francis Group, 1988), 144; Neil Smith, American Empire: Roosevelt’s Geographer and the Prelude to Globalization (University of California Press, 2003).

[12] For more on this history see Ruohong Li, “From Harvard Yard to Divinity Avenue: The Harvard-Yenching Institute’s Two Homes,” Harvard-Yenching Institute Working Paper Series, 2021.